Segregation Across the Lifecycle

Persistent racial and ethnic segregation is a common feature across most US metropolitan areas. One anecdotal pattern is that young White adults often move into diverse neighborhoods only to move to more homogenous suburban neighborhoods after having kids. In this post, I begin by testing the extent to which this pattern holds true in reality; does the degree of segregation within metropolitan areas differ by the age of residents?

In subsequent posts, I will then test whether this means that changes in preferences around having children are important drivers of continued segregation or whehter these patterns can be explained by other factors such as increasing income gaps between white and non-white residents by age or generation-based preferences.

Data: I use data from the 2010 census available through NHGIS, which recorded population counts by age and race/ethnicity for all census tracts in the United States.

What do I find: The graph below shows the average White share of the average White resident of the five most populous metropolitan areas in the US. In each metro, the White share of White residents’ neighborhoods peak between the ages of 5-17 and are at their lowest points between the ages of 20-29. These differences, while not enormous, are meaningful—for instance in the New York City metro area, the average White 10-14 year old lives a neighborhood that is 75% White, while the average 25-29 year old lives in a neighborhood that is 66% White.

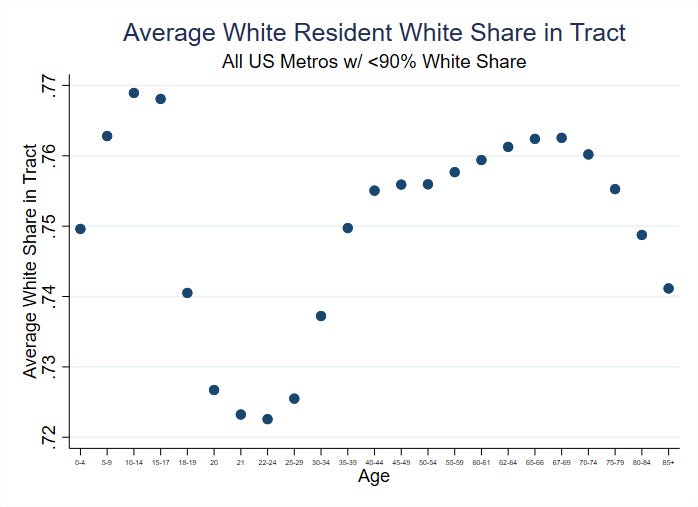

Roughly similar, though slightly less extreme patterns if we average across all US metros [Note: I excluded metros with a White share greater than 90% as these metros have little opportunity for moving to areas with diversity.]

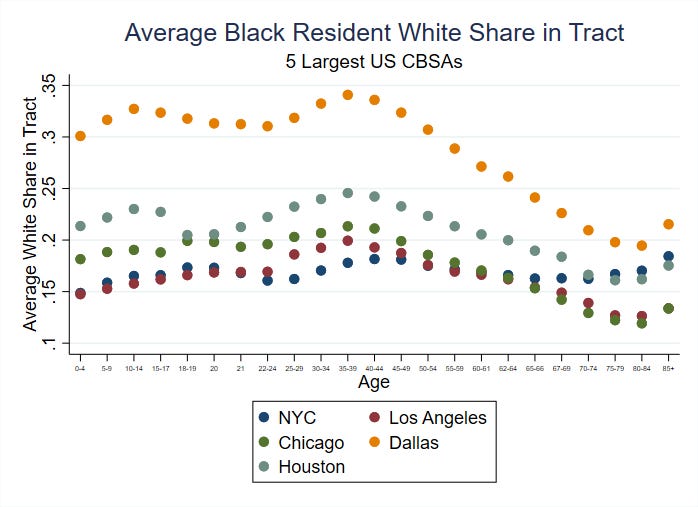

We can look at similar graphs for Black and Hispanic residents exposure to White neighbors. Black residents experience a completely different pattern than White residents, with exposure to white neighbors rising linearly until around age 40-45, after which there is a sharp decline. Conversely, the pattern for Hispanic residents mirrors that of White residents, but is more attenuated. In none of the five largest metros is there more than a 5 percentage point difference between the age group with the highest exposure to White residents and the age group with the lowest exposure.

These patterns provide some suggestive evidence that children may shift White parents’ preferences in ways that lead them to live in more homogenous environments. But of course that is not the only explanation for these results—it could be that income gaps between White, Black and Hispanic residents grow over time and predominantly White neighborhoods are disproporationely higher income. It could also be that there are cohort effects in White residents preferences about where to live and that is what are driving these results (i.e. when today’s White 25 year olds become 50, they will live in much more diverse neighborhoods than today’s 50 year olds). I will investigate these hypotheses in the next post.